ZENPTY.

Ancel Keys and the Diet-Heart Hypothesis: A Deep Dive into Flawed Science

Aug 26, 2024

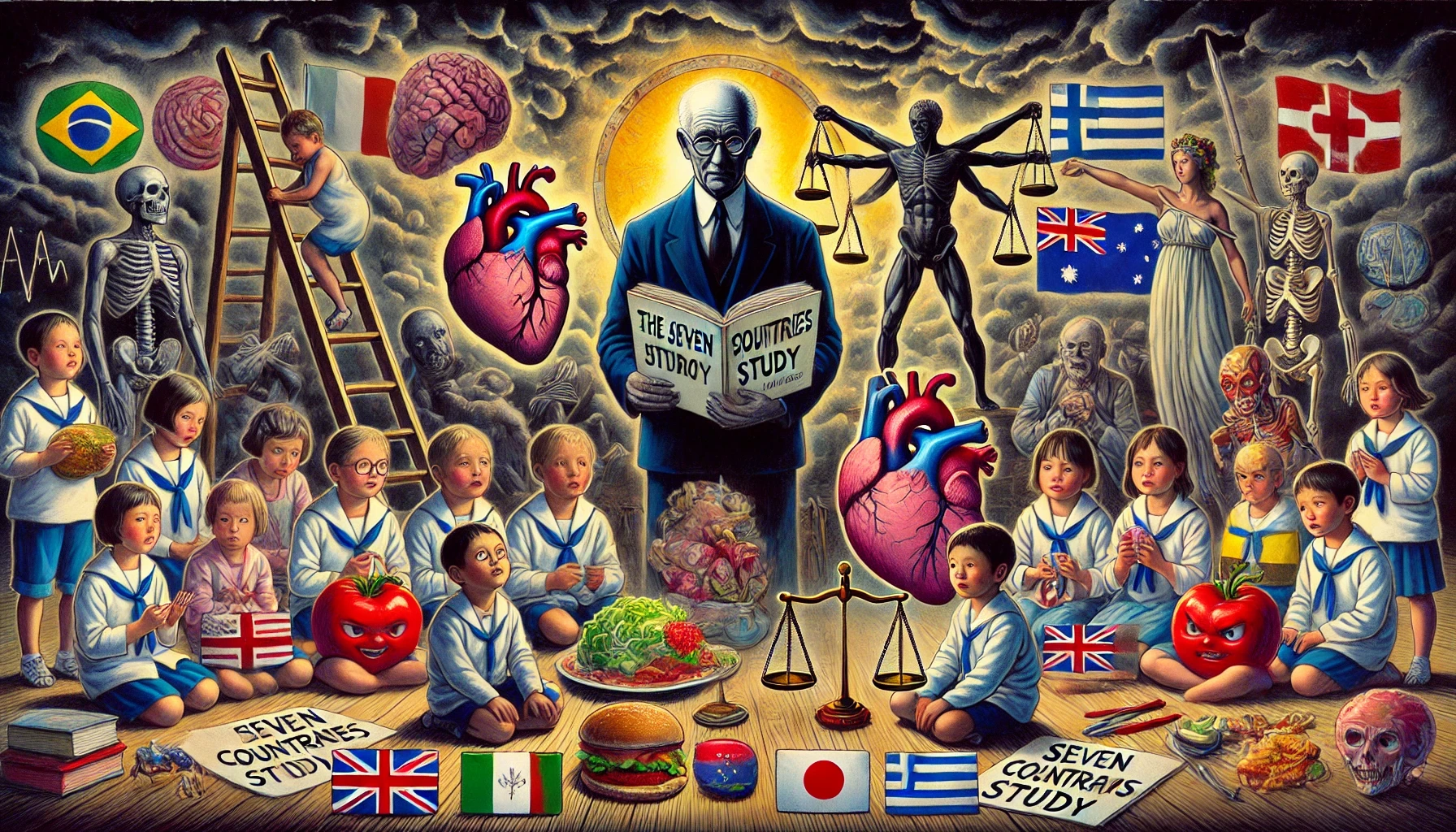

The “diet-heart hypothesis,” introduced by Ancel Keys in 1952, argued that dietary fat caused cardiovascular disease by forming cholesterol clots. Despite the enormous attention it received, it also faced significant criticisms, including accusations of cherry-picking data to manipulate the experiment. Undeterred, Keys was ready for a counterattack. Let’s continue our discussion from “The Big Fat Surprise” and explore the landmark experiment that influenced our avoidance of good fats for over half a century.

In 1956, Keys launched “The Seven Countries Study” with an annual grant of $200,000 from the US Public Health Service—an enormous sum for a single project at the time. He planned to follow approximately 12,700 middle-aged men in mostly rural populations across Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia, Finland, the Netherlands, Japan, and the United States.

The results of the Seven Countries Study first appeared in a 211-page monograph published by the American Heart Association (AHA) in 1970, followed by a book from Harvard University Press.

Keys found, as he had hoped, a strong correlation between the consumption of saturated fat and deaths from heart disease. The results suggested that although Finnish lumberjacks and Greek farmers ate roughly the same amount of fat, it was the type of fat that mattered. According to the study, the more saturated fat one ate, the greater the risk of having a heart attack. Saturated fat comprised only 8 percent of calories eaten by the Cretans, compared to 22 percent for the Finns. These findings appeared conclusive and seemed to offer a definitive answer to Keys’s critics.

But upon closer inspection, the study was fraught with issues.

Firstly, Keys picked countries likely to confirm his hypothesis. Critics pointed out that he should have included countries like Switzerland and France, where people consumed healthy amounts of saturated fat but had low heart attack rates. Instead, he chose countries that supported his hypothesis.

Secondly, even within his chosen countries, the correlation between saturated fat and heart disease didn’t hold up well. People eating diets low in saturated fat had just as high a risk of dying as their fat-consuming counterparts. The longest-living individuals in the study were in Greece and the United States, and their longevity showed no relationship to the amount of fat or saturated fat they consumed, nor to their blood cholesterol levels.

Thirdly, the data collection methods were inconsistent and unreliable. Of the 12,770 participants, only 499 (3.9 percent) had their food intake evaluated. Data collection varied widely among nations: in the United States, a one-day sample was taken for 1.5% of the men, whereas in other countries, data were collected for up to seven days. Even within a country, methods varied. For example, in Greece, three different chemical methods were used to analyze fats in food samples, leading to inconsistent results.

One survey on Crete fell during the forty-eight-day fasting period of Lent, when participants abstained from all animal-origin foods, including fish, cheese, eggs, and butter. This would obviously undercount saturated fat intake, yet the study made no attempt to differentiate between fasters and non-fasters.

Beyond these data issues, the Seven Countries Study had a significant structural limitation: it was an epidemiological investigation, meaning it could only show an association, not causation. It could show that two elements occurred together, but it couldn’t establish a causal connection. At best, Keys’s study could show an association between a diet low in animal fats and minimal rates of heart disease, but it couldn’t prove that diet caused the disease.

These issues were carefully hidden and took years to uncover. Keys published most of the data in a Dutch nutrition journal called Voeding, not in mainstream British or American publications where he published most of his other Seven Countries papers. He knew this would ensure the data went unnoticed. There is a record of him complaining to colleagues that his paper in Voeding received no international attention, unlike his other papers.

Having buried concerns about his data and its limitations, Keys aggressively promoted his study’s main takeaway: that eating saturated fat leads to high cholesterol, and high cholesterol leads to heart disease. With the Seven Countries Study ostensibly supporting his claims, Keys could defend his idea more forcefully. As Time magazine reported, a Philadelphia physician said, “Every time you question this man Keys, he says, ‘I’ve got 5,000 cases. How many do you have?’” While scientists knew an association didn’t prove causation, the sheer magnitude of data in Keys’s study granted him unusual stature, and he reaped the benefits.

In our next discussion, we will see how Keys managed to embed the quasi-science of the diet-heart hypothesis into the American psyche through politics and media.

Next: Silencing Dissent: How Ancel Keys' Hypothesis Dominated Nutrition Science

This is part 4 of the series on “The Big Fat Surprise.”

A Carnivore Journey: How Letting Go of Carbs Opened New Doors

Nutritional Myths and Nuclear Risks: The Parallel Stories of Regulatory Capture

Silencing Dissent: How Ancel Keys' Hypothesis Dominated Nutrition Science

Unmasking the Villain: Ancel Keys and the War on Saturated Fat

From Eisenhower to Endo: The Evolution of Heart Health Myths

Red Meat, Cholesterol, and Fat: Challenging Conventional Wisdom