ZENPTY.

The Spiritual Essence of Mochi: A New Year's Journey in Japan

Mar 15, 2024

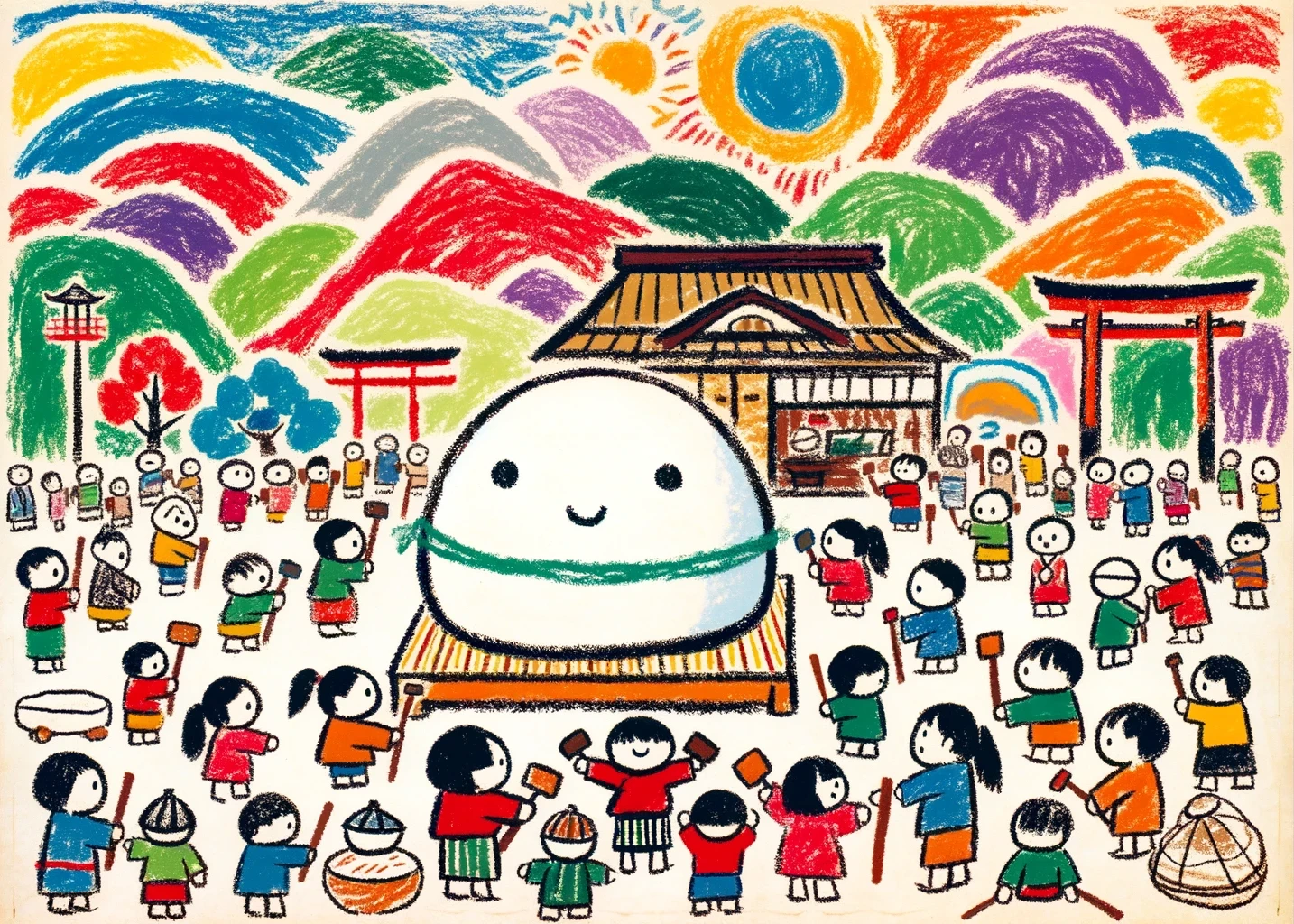

Celebrating the New Year in Japan brought a unique twist this year. Gathered with family, in-laws, and neighbors, I found myself at the heart of a traditional mochi-pounding ceremony. This experience was ignited by my father-in-law's enthusiasm to showcase his newly acquired mortar and mallet, crafted from the esteemed Japanese zelkova wood, a gift from his elderly neighbor.

As I stood there, a steaming dough of rice waiting inside the mortar, I was about to partake in "mochitsuki," a cherished New Year's ritual. This process involves a rhythmic dance between the mallet-wielder and the dough-puller – a test of skill and agility, especially avoiding a mallet-meets-fingers mishap!

Admittedly, wielding the enormous mallet was a feat for me. Accustomed to the lightweight demands of my Tokyo lifestyle, my arms were hardly prepared for this 7kg (15-pound) challenge. Just two days into the New Year, and I was already feeling every muscle in my body. How about we switch to sake and relaxation?

This event led me to ponder the connection between mochi and spirituality. My previous encounters with mochi were confined to the indulgent, dopamine-boosting versions found in grocery store freezers. Yet, here I was, discovering a deeper, more spiritual layer to mochi beyond its 'candified' convenience store and subscription box counterparts.

Why do the Japanese engage in this laborious "mochitsuki" ritual every New Year, risking injury for a simple, unsweetened treat? Growing up in a secular environment and constantly on the move, I lacked a firm grasp of Japanese spiritual traditions. Seeking answers, I turned to an external source – a website by a Japanese company known for making traditional fish cakes.

According to ethnologist Hiromichi Kubota, the New Year's celebration in Japan honors Toshigamisama, the year god. This concept was foreign to me – was Toshigamisama akin to a local deity or a mythical figure like Santa Claus? This left me more puzzled than enlightened.

Japan's polytheistic culture, deeply rooted in Shintoism and intertwined with Buddhism, respects a multitude of gods and spirits. This blend of beliefs shapes Japanese practices, including the veneration of ancestors through Buddhist memorial services and the belief that the soul joins a collective ancestral spirit after 32 years.

To welcome Toshigamisama during the New Year, the Japanese decorate their homes with "kadomatsu" – traditionally made of pine but now often bamboo. This acts as a residence for the spirit. Additionally, "shimenawa," a straw decoration made from newly harvested rice, is used to welcome the spirit.

The rounded mochi, painstakingly made during mochitsuki, symbolizes the ancestral spirit. It's an embodiment of our love and effort, offered to Toshigamisama, and consumed with family to absorb its spiritual essence.

That day, each of us took turns at mochi-making, resulting in a plain yet profound final product. Devoid of commercial sweetness, it was served simply with soy sauce, nori, kinako powder, red bean paste, and in a comforting ozoni soup.

Mochi, in essence, represents the joy of shared memories and the spiritual glue binding modern Japanese society. This experience, blending the physical and the spiritual, offered a profound insight into a culture steeped in tradition and respect for the past.

A Carnivore Journey: How Letting Go of Carbs Opened New Doors

Nutritional Myths and Nuclear Risks: The Parallel Stories of Regulatory Capture

Silencing Dissent: How Ancel Keys' Hypothesis Dominated Nutrition Science

Ancel Keys and the Diet-Heart Hypothesis: A Deep Dive into Flawed Science

Unmasking the Villain: Ancel Keys and the War on Saturated Fat

From Eisenhower to Endo: The Evolution of Heart Health Myths